Written By His Students

Jacob Barrett

Adam Gjesdal

Bill Glod

Keith Hankins

Brian Kogelmann

Ryan Muldoon

John Thrasher

Kevin Vallier

Chad Van Schoelandt

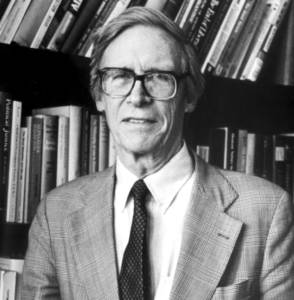

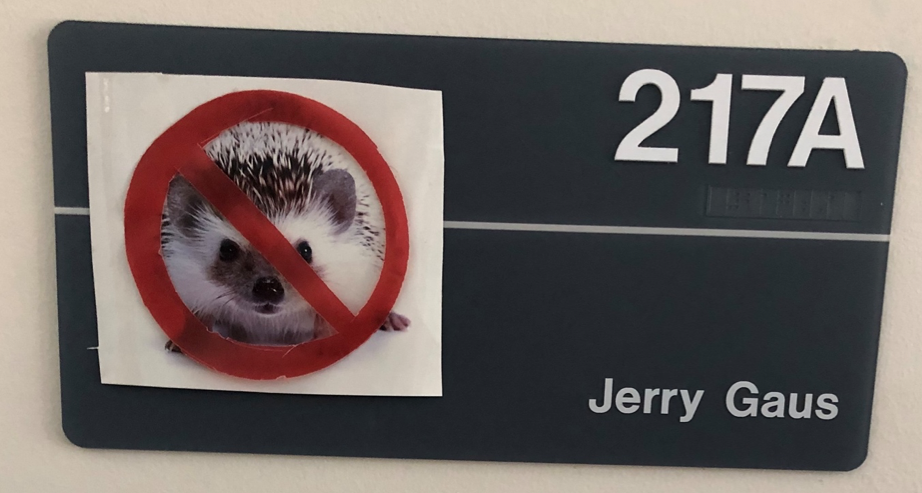

It is difficult to describe Jerry Gaus’s views and accomplishments in part because he was so prolific, having authored nine books comprising roughly 3,000 pages and more than a hundred published papers. Moreover, his work was wide-ranging and interdisciplinary. Jerry was critical of what he sometimes called “hedgehogosity,” the tendency for political philosophers to define themselves in terms of well-defined schools or even a single supreme value. In contrast to the hedgehog’s narrowness, consider how Jerry describes his work in The Order of Public Reason (2011, xiv–xv): “we will have to grapple with the insights of, among many others, Hobbes, Hume, Kant, Rousseau, J. S. Mill, T. H. Green, P. F. Strawson, Kurt Baier, S. I. Benn, R. M. Hare, F. A. Hayek, David Gauthier, Alan Gewirth, Kenneth Arrow, John Rawls, James Buchanan, and Amartya Sen. We will draw on game theory, experimental psychology, theories of emotion and reasoning, axiomatic social choice theory, constitutional political economy, Kantian moral philosophy, prescriptivism, and the concept of reason and how it relates to freedom in human affairs.”

Jerry (2011, xv) noted that his “work is often categorized under the ‘libertarian’ label since I argue that human freedom is terribly important, that coercive interferences infringe freedom and so must always be justified to the person who is being coerced.” He wrote this not to embrace a libertarian label, but to reject it, as Jerry stressed his concerns with coercion came from his friend and co-author Stanley Benn, an Australian Labor Democrat. Indeed, Jerry’s bête noire was political ideology of all kinds, including libertarianism, because adopting them detracts one from “the truth business,” as his advisor John Chapman taught him.

Jerry understood himself to be working in a tradition with an ongoing, active research agenda for a scholarly community, teaching us about the complexities of our social world, rather than looking for opportunities to reinforce our biased ways of understanding it. For this reason, we want to emphasize not merely Jerry’s accomplishments, like his major books, but also the ongoing projects and areas in which he played a pivotal role.

Public Reason

Jerry is best known for his work in the public reason tradition, particularly as he was the leading figure in what has come to be known as convergence liberalism. He had worked on the idea of public reason at the same time as Rawls was – during the 1980s. Jerry produced his first work in the area in 1990: Value and Justification.[i]

Throughout his career, Jerry was heavily influenced by the great social contract theorists – Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, and Kant – as well as contemporary theorists like Rawls and David Gauthier. From very early on, Jerry recognized that living in a complex social order required a kind of agreement amongst its members on the terms of social life. As he understood them, the social contract theorists recognized that engaging in moral reasoning about how to live from a purely first-personal point of view was bound to lead to destructive conflict. So, in a deep study of how humans make value judgments, the nature of the moral emotions and a theory of moral maturation, Jerry argued that we must come to move beyond the first-personal point of view and to integrate a social perspective into our individual perspectives. Only in this way can humans successfully cooperate with one another. Taking the perspective of others was also a pre-requisite for maintaining our personal relationships. Doing so is central to sustaining valuable relations of love, friendship, and trust. All relationships require that we follow certain kinds of rules and moral requirements that involve taking the perspective of others into account.

The doctrine of public reason is derived from Jerry’s account of personal values and the norms internal to personal relationships. We pursue public justifications for our shared rules of social life in order to ensure that the rules are acceptable to all, such that persons can related to one another by way of complying with those rules. Jerry would stress the importance of shared reasoning in helping us live together. Yet, even there, we find a role for pluralistic and diverse reasoning in formulating a justification for our moral demands on one another, though the theme was not as central as it would become in later work.

As Jerry was working on his next book, Justificatory Liberalism, he came to embrace more pluralistic forms of reasoning, allowing diverse reasoning to supplement shared reasoning more and more. In the terms of Jerry’s good friend and fellow public reason theorist, Fred D’Agostino, Jerry had moved away from the mainstream “consensus” model of public reason of expecting an agreement about which reasons could be appealed to in justifying social and political power and coercion, and supplanted it with a “convergence” view where diverse reasons could figure into the justification of coercive political power. Yet even here, Jerry adopted a principle of sincerity that required citizens to engage in shared reasons in justifying moral and political claims to one another.

Over the next fifteen years, in the build-up to The Order of Public Reason, Jerry would increasingly stress the incompleteness of the social contract tradition. The difficulty with mainstream ideas of public reason is that they supposed a society could reach an agreement about principles of morality and justice. But it became a central theme of OPR that this was an unrealistic expectation. Jerry also stressed, in contrast to Justificatory Liberalism, that we could not rely on the political process alone in choosing between proposals that could only be “inconclusively” justified to all. Instead, we would have to appeal to social evolution in order to come upon concrete agreements. Kant and Rawls would have to join forces with Hume and Hayek. An “order of public reason” would not be a “deliberative democracy” that would narrow our disagreements to consensus, on reasons or on public policy; rather, it was a complex order of “social-moral rules” in which the political process played a central, but quite limited part.

Along the same lines, Jerry began to address religious reasoning more carefully, and moved away from the “privatization” approach. Once we allow for diverse reasoning, Jerry acknowledged, we must include the reasoning of people of faith. Jerry therefore was among the fairly narrow class of historical liberals who saw religious reasoning and religious discourse as source of social progress rather than social regression. Public reason must be pluralistic, diverse, and face up to indeterminacy and interminable disagreement; this put Jerry in a class almost by himself, such that his public reason project was an almost staggering departure from the rest of the ever-expanding public reason literature. The themes in The Order of Public Reason would receive the most uptake from his expanding number of graduate students, but his work on religion and politics was so distinctive that it attracted a great deal of attention, especially “The Roles of Religious Conviction in a Publicly Justified Polity” which was his most cited article.

By the end of his career, however, Jerry had come to worry that even his account in the book was insufficiently accommodative of moral diversity. People disagree not only about the inherent morality or justice of different rules, but also about how much they value reconciling with others or living together under publicly justified rules—and even about which others they seek to reconcile with. In “Self-organizing Moral Systems: Beyond Social Contract Theory” and The Open Society and its Complexities (forthcoming), he therefore began to investigate and model the conditions under which individuals who disagreed in all of these ways could nevertheless coordinate on publicly justified rules, rather than polarize or split apart.

Moral Psychology and Social Morality

Jerry would argue in The Order of Public Reason that moral philosophers had all too often expected to give a single analysis or explanation of all moral truths. But he thought it was critical to distinguish between the many different domains of the normative, and he tended to concern himself with one part of it – what Jerry called “social morality,” or the norms or rules of conduct that members of a society may hold one responsible for violating and punish for defecting.

The idea of “social morality” is central to The Order of Public Reason. Jerry credits the idea to philosophers like P.F Strawson, Kurt Baier, and David Gauthier. But its lineage extends at least as far back as the Scottish Enlightenment, to David Hume’s artificial virtues and Adam Smith’s rules of justice. Social morality is embodied in a shared system of interlocking descriptive and normative expectations that guide our social interactions. This system includes laws the state promulgates and coercively enforces. But it extends more deeply into the fabric of social life to include complex informal norms that are not coercively enforced by the state. We implicitly act on these informal norms when we walk down the street or make a purchase. What sustains these informal norms is not coercive enforcement but internalization and the reactive attitudes—for in violating them we become appropriate objects of guilt and resentment. These informal norms have much in common with Humean conventions. They are objects of something like common knowledge: a norm of walking on the right side of the street exists only if nearly everyone knows others expects them to walk on the right. And, like Humean conventions, these norms perform an important function in human life of making mutually beneficial cooperation possible.

After The Order of Public Reason, Jerry would develop his analysis of social morality. In “The Priority of Social Morality” and his forthcoming The Open Society and Its Complexities, he shows how work in evolutionary anthropology and behavioral and experimental economics substantiates the claim that norms of social morality form the basis of small-scale human social orders. His “On Dissing Public Reason: A Reply to David Enoch” takes pains to clarify how the idea of social morality is distinct from, and so ought not be conflated with, more “absolute” notions of morality and normativity, often presumed by philosophers in discussions of human rights. In “Moral Learning in the Open Society,” co-authored with Shaun Nichols, he provides experimental evidence that social morality includes a principle of natural liberty, which permits novel action types whenever they are not expressly (or implicitly, via clear analogy) prohibited by existing rules.

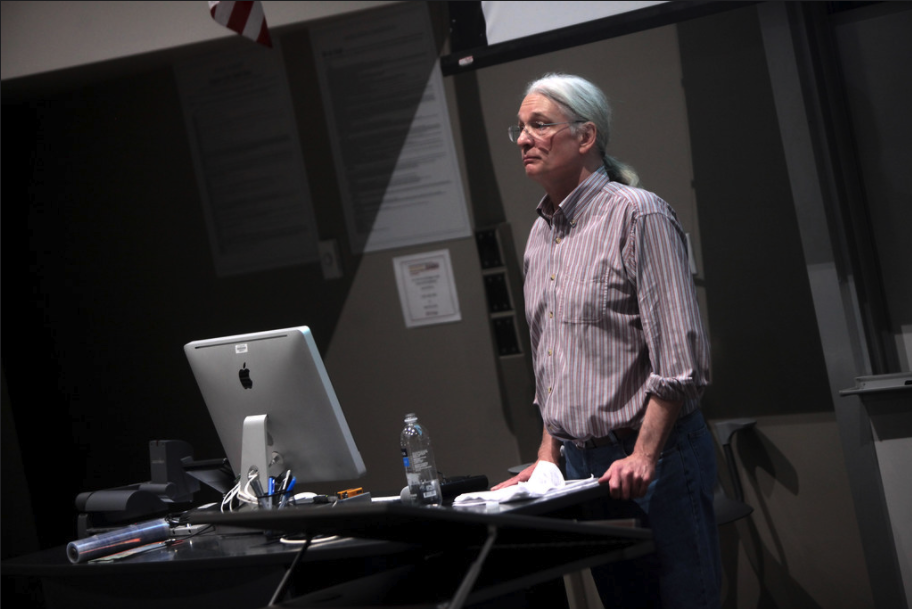

Philosophy, Politics, and Economics: The Gausian Method

Jerry was a champion of the PPE approach to understanding society and our place in it. Throughout all of his work, Jerry showed what we might call an “integrative approach” to PPE in action. This approach, which in some ways reaches back to the early political economists like David Hume and Adam Smith who were simultaneously philosophers, political theorists, and political economists. Indeed, the department that he chaired at the time of his death—The Department of Political Economy and Moral Sciences—illustrates this integrative, interdisciplinary focus in it name. Jerry also ran the Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and Law (PPEL) major at the University of Arizona. PPE education as well as research was a central concern for Jerry. The reason is simple. Jerry believed, rightly in our view, that important social, political, and moral problems, which also animated significant historical figures, can’t be understood, let alone answered, if they are viewed from a single disciplinary lens. To really make progress on the crucial questions of social life, we need the tools and complementary lenses that come from an integrated PPE approach. PPE also helps to mitigate what he thought was the tendency of political philosophy to become ideological.

Aside from his own work, his leadership in the burgeoning PPE movement, and his pedagogy, Jerry also did important work to make the world safe for PPE. An important step in this direction was the founding of the journal Politics, Philosophy, and Economics, which he edited with his good friend Fred D’Agostino to establish it as a premier venue for interdisciplinary work. Alongside the journal, many other venues have since arisen to cultivate PPE research. One of these is the PPE Society, of which Jerry was an active participant. At the time of his death, Jerry was in the process of writing, with John Thrasher, a new textbook on the methods and theory of PPE for Princeton University Press (following up on the original edition, archived here). The aim of this book is to make it easier for anyone to teach PPE to undergraduates, opening up the possibilities for a more integrative and diverse approach to the social sciences and humanities.

Complexity and Ideal Theory

A central theme of much of Jerry’s later work is social complexity and its implications for political philosophy. Many believe that a conception of the ideally just society (“the ideal”) orients the pursuit of justice by serving as a long-term goal for reform. But in The Tyranny of the Ideal, Jerry draws on complexity theory to interrogate and cast doubt on this view. In the absence of complexity—roughly, interactions between different social elements—local improvements to our society would perfectly correlate with steps toward the ideal, so there would be no need to explicitly identify and pursue the ideal as a long-term goal. In the presence of complexity, this correlation breaks down, so there is a more obvious need to orient ourselves toward the ideal. But we now run into a serious epistemic difficulty: in general, we can be much less confident about the effects of more radical changes than more modest changes to complex systems. Whenever one is tempted to pursue one’s conception of the ideal, one therefore faces The Choice: should one pursue a relatively certain local improvement, or a far less certain ideal? Jerry argues that the only social-epistemic conditions under which we might be confident enough about ideal justice to responsibly opt for its pursuit would be found in an open, diversity-accommodating society in which widespread disagreements about justice would, ironically, render the pursuit of the ideal impossible. He therefore recommends that we give up on the ideal in favor of an Open Society that everybody sees as satisfactory though nonideal.

Jerry elaborates on this theme in his forthcoming book, The Open Society and its Complexities, which undertakes a Hayek-inspired investigation into the prospects of justification and governance in the Open Society. Standard moral theories and social contract models, Jerry argues, are ill-equipped to justify the rules of the Open Society, since they cannot accommodate its degree of “autocatalytic” diversity and complexity—whereby diversity begets complexity, which begets further diversity, and so on. Instead, justification must proceed from the bottom-up: from real individuals self-organizing around publicly justified rules.

But this need for emergent self-organization, Jerry claims, should not lead us to neglect the possibility and importance of governance. Due to social complexity, our ability to govern a social system decreases at larger scales and over longer time horizons, so rather than treating governance as a unitary phenomenon, we must carefully attend to different modes of governance. For example, while at the macro-level we are limited to setting “rules of the game” that facilitate self-organization, at the meso-level we may solve strategic dilemmas, and at the micro-level we may pursue particular policy goals. Yet complex systems are also characterized by “reflexivity”: the government is just one agent in the system, to which others respond, and to which the government must then respond in turn. Typically, then, governance is more effective when individuals willingly go along with the government, as occurs in the presence of public justification.

Jerry also worked through these issues in a number of relevant papers, including “Searching for the Ideal: The Fundamental Diversity Dilemma” (with Keith Hankins), “Political Philosophy as the Study of Complex Normative Systems,” “The Complexity of a Diverse Moral Order,” “Morality as a Complex Adaptive System: Rethinking Hayek’s Social Ethics,” and “What Might Democratic Self-governance in a Complex Social World Look Like?”

New Diversity Theory

Jerry was the leading figure in what some have termed “The New Diversity Theory.” Along with Fred D’Agostino, Jerry was an early advocate of the idea that fundamental moral diversity is not merely a problem to be managed, but a resource to be leveraged. Diversity makes our social lives more complex, and stability more difficult to achieve, but it is also an engine for discovery and progress. Diversity enables us to find better ways of living together, and adapt to new situations more readily, even as it invariably generates sources of conflict. Jerry thought that this was a necessary course correction for political philosophy. Instead of abstracting away from our differences to examine an ideological project in its purest form, he thought we needed to understand and celebrate ways that very different people can live together and solve problems cooperatively. Indeed, exploring social diversity and its consequences is where we can find many of the most interesting problems in political philosophy and PPE.

This thinking is most evident in The Order of Public Reason, The Tyranny of the Ideal, and his final book, The Open Society and its Complexities, as well as papers such as “Between Discovery and Choice: The General Will in a Diverse Society”, “Searching for the Ideal: The Fundamental Diversity Dilemma” (with Keith Hankins), “The Complexity of a Diverse Moral Order”, and “Is Public Reason a Normalization Project? Deep Diversity and the Open Society.”

Just as important as his own contributions to the New Diversity Theory were his efforts to elevate others who were developing their own approaches to this project. Some, like Fred and Paul Dragos Aligica were already very established scholars, but Jerry went out of his way to bring attention to younger scholars, such as Ryan Muldoon, Michael Moehler, and Julian Müller. He also trained a number of philosophers who have already established themselves as figures in this area, such as Chad Van Schoelandt, John Thrasher, Kevin Vallier, Keith Hankins, and Brian Kogelmann. Jacob Barrett, Adam Gjesdal, Phil Smolenski, Alex Motchoulski and Alex Schaefer are more recent students of Jerry working in this area.

In many ways, the New Diversity Theory is the culmination of themes in Jerry’s work, as the project is in essence a research program, a kind of new paradigm of political philosophy. The New Diversity Theory comes with new sets of interdisciplinary tools, new attitudes towards certain kinds of social phenomena, and different expectations about what philosophical reasoning can accomplish. It is our belief that the New Diversity Theory is one of the most promising avenues for new research in political philosophy.

History of Philosophy: The Social Contract Tradition

Jerry’s work on the New Diversity Theory colored the way he read the history of political thought. Political philosophy, he would tell his students, began with Hobbes. This is because Hobbes was concerned with the same set of problems that the New Diversity Theory takes as its focus. For many, this will be a surprise. Hobbes, we are all taught, is the theorist of self-interest, who teaches that human conflict is generated by humanity’s darker motives. Jerry did not like this reading. Instead of focusing on chapter thirteen of Leviathan, he spent much time analyzing chapter five, where Hobbes says that, due to the fallibility of human reason, “parties must by their own accord set up for right reason the reason of some arbitrator or judge.” In other words, the problem of conflicting private judgment, according to Hobbes, can only be solved with some kind of public reason. Jerry read Locke in a similar manner, where conflict arises from conflicting private judgment, and the solution is to set up some kind of public method of reasoning that allows persons to resolve their disputes, and live peacefully.

Jerry’s contributions to the history of the social contract tradition include: “Locke’s Liberal Theory of Public Reason,” “Public Reason Liberalism,” “Hobbes’s Challenge to Public Reason Liberalism,” and “Hobbesian Contractarianism, Orthodox and Revisionist.” Perhaps his most important contribution is the edited volume (with Piers Norris Turner) Public Reason in Political Philosophy: Classical Sources and Contemporary Commentaries. The idea of the volume is to show how the problem of diversity and conflicting moral judgment can be found not only in the social contract tradition, but in the work of other important historical figures, such as Hume, Hegel, Bentham, and Mill. And indeed, in that edited volume, Jerry located the idea of public reason in these early figures, making Rawls a more minor figure in the development of public reason liberalism.

Jerry thought that understanding the history of political philosophy was key to crafting its future and making progress on pressing questions. He frequently pushed his own research program forward by drawing on insights from a vast range of thinkers from the past, some of whom, like Hobbes, are well-known, but others, like T.H. Green (as Jerry explored in “Green’s Rights Recognition Thesis and Moral Internalism”), have been left behind.

Teaching and Mentoring

While most people know Jerry through his publications, we want to conclude by noting his tremendous accomplishments as a teacher and mentor. The University of Arizona recognized Jerry’s excellence in this area with the university’s Award for Teaching and Mentoring in Graduate Education in 2015.

Jerry is famed for holding his students to exacting standards, while providing the students with extensive support to develop and meet those standards. His support and expectations impelled students to tremendous productivity, expeditious completion of the PhD program, and vibrant careers. Importantly, Jerry’s standards were exclusively those of scholarship and argumentative rigor, never demands on their research questions or conclusions. Central to Jerry’s approach to teaching was encouraging his students to explore the issues they saw as meriting exploration and to come to their own conclusions.

Jerry’s devotion to teaching manifested in many ways, including that he frequently taught graduate seminars as overloads beyond his teaching obligations.

Lastly, we’ll emphasize that Jerry approached philosophy as a cooperative venture. Some note that Jerry seemed to never reject an invitation to contribute to a collection. A major part of this was that when Jerry received such invitations, he often considered his graduate students and asked if they were interested in collaborating on the paper. These collaborations provided highly enjoyable and valuable opportunities to engage in the substantive issues and to learn the craft of writing. Likewise, deep discussions of philosophic problems frequently led to collaborations on important peer-reviewed articles.

In this way, the philosophic projects exemplify some of the core insights of Jerry’s philosophic views. New members of the community contribute to a cooperative surplus and the benefits are enhanced with increased perspectival diversity of the cooperators. We hope that you will see Jerry’s work as not merely providing incredible insights, though it certainly does that, but also as providing resources for ongoing research projects and a warm invitation to join in those explorations.

References

Books

Gaus, Gerald. 1983. The Modern Liberal Theory of Man. New York: Palgrave.

———. 1990. Value and Justification: The Foundations of Liberal Theory. Cambridge University Press.

———. 1996. Justificatory Liberalism: An Essay on Epistemology and Political Theory. Oxford University Press.

———. 1999. Social Philosophy. Routledge.

———. 2000. Political Concepts and Political Theories. Westview Press.

———. 2003. Contemporary Theories of Liberalism: Public Reason as a Post-Enlightenment Project. Sage.

———. 2011. The Order of Public Reason: A Theory of Freedom and Morality in a Diverse and Bounded World. Cambridge University Press.

———. 2016. The Tyranny of the Ideal: Justice in a Diverse Society. Princeton University Press.

———. 2021 [expected] The Open Society and Its Complexities. Oxford University Press.

Turner, Piers Norris, and Gerald Gaus, eds. 2017. Public Reason in Political Philosophy: Classic Sources and Contemporary Commentaries. Routledge.

Articles Mentioned (see Gaus’s CV for much more)

“Green’s Rights Recognition Thesis and Moral Internalism.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations, vol. 7 (2005): pp. 5-17.

(with Kevin Vallier) “The Roles of Religious Conviction in a Publicly Justified Polity: The Implications of Convergence, Asymmetry and Political Institutions.” Philosophy & Social Criticism, vol. 35 (2009): pp. 51-76.

“Between Discovery and Choice: The General Will in a Diverse Society,” Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice, vol. 3 (2011): pp. 70-95.

“Hobbes’s Challenge to Public Reason Liberalism,” In Hobbes Today, edited by S.A. Lloyd. Cambridge University Press, 2013: pp. 155-177.

“Hobbesian Contractarianism, Orthodox and Revisionist.” In The Continuum Companion to Hobbes, edited by S.A. Lloyd. Bloomsbury, 2013: pp. 263-278.

“On Dissing Public Reason: A Reply to Enoch.” Ethics, vol. 125 (2015): pp. 1078-1095.

“Public Reason Liberalism.” In The Cambridge Companion to Liberalism, edited by Steve Wall. Cambridge University Press, 2015: pp. 112-40.

“Is Public Reason a Normalization Project? Deep Diversity and the Open Society.” Social Philosophy Today, vol. 33 (2017): pp. 27-55.

(with Shaun Nichols) “Moral Learning in the Open Society: The Theory and Practice of Natural Liberty.” Social Philosophy and Policy, vol. 34 (2017): pp. 79-101.

(with Keith Hankins) “Searching for the Ideal: The Fundamental Diversity Dilemma.” In Political Utopias, edited by Michael Weber and Kevin Vallier. Oxford University Press, 2017: pp. 175-201.

The Complexity of a Diverse Moral Order.” The Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy, vol. 16 (2018): pp. 645-779.

“Locke’s Liberal Theory of Public Reason.” In Public Reason in the History of Political Philosophy, edited by Piers Norris Turner and Gerald Gaus. Routledge, 2018: pp. 163-83.

“Political Philosophy as the Study of Complex Normative Systems.” Cosmos + Taxis, vol. 5 (2018): pp. 62-78.

“The Priority of Social Morality.” In Morality, Governance, and Social Institutions: Reflections on Russell Hardin, edited by Thomas Christiano, Ingrid Creppell and Jack Knight. Palgrave, 2018: pp. 23-57.

“Self-organizing Moral Systems: Beyond Social Contract Theory.” Politics, Philosophy and Economics, vol. 17 (2018): pp. 119-147.

“Morality as a Complex Adaptive System: Rethinking Hayek’s Social Ethics.” The Oxford Handbook of Ethics and Economics, edited by Mark D. White. Oxford University Press, 2019: pp. 138-159.

“What Might Democratic Self-governance in a Complex Social World Look Like?” 56 San Diego Law Review, vol. 56 (2019): pp. 968-1012.

—

[i] This was his second book, coming nine years after a short study of six figures in the liberal tradition – J.S. Mill, T.H. Green, Bernard Bosanquet, L.T. Hobhouse, and John Rawls – called The Modern Liberal Theory of Man (1983).