I’d like to return to my ongoing interest in anti-liberal doctrines, especially the new Catholic integralism. I think it might be worthwhile exploring how the political liberalism of John Rawls clashes with integralism, and attempt to make the criticism plausible. The integralists may still deride it, and how!, but it will serve for clarificatory purposes.

I now believe that the most central difference between Catholic integralism and Rawlsian political liberalism is their differing views of the rationality of moral disagreement. Political liberalism indeed presupposes that deep disagreement about the requirements of morality is natural to human beings; that it is the inevitable result of the free exercise of human reason. Catholic integralists deny this. People may disagree about morality, but that is because of sin—a failure, culpable or no—to receive the grace of God by way of the Catholic Church directly, and through political institutions partly governed by the Church. I think for the integralists, two members of an integralist society with a modest degree of natural and supernatural virtue will tend to agree about the requirements of the natural law for human behavior.

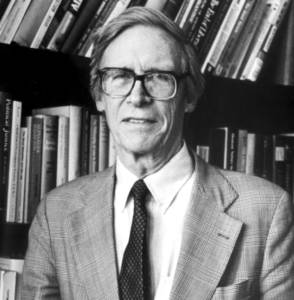

John Rawls

This is not what Rawlsians would consider the free exercise of human reason, of course, but it is the condition that integralists would regard as the freest, and indeed this points to another deep difference: about the nature of freedom. Rawls likes negative liberty, but he also likes positive liberty, and indeed is friendly to the idea of the freedom that is achieved by the use of reason. But the integralist will insist that the exercise of human reason is only truly free when it has been, at least to some extent, dusted off by the reception of the sacraments.

So, here’s one of Rawls’s first comments on integralist-type views. The theory of rational moral disagreement is in the driver’s seat and indeed necessitates the much-derided idea of the reasonable:

The advantage of staying within the reasonable is that there can be but one true comprehensive doctrine, though as we have seen, many reasonable ones. Once we accept the fact that reasonable pluralism is a permanent condition of public culture under free institutions, the idea of the reasonable is more suitable as part of the basis of public justification for a constitutional regime than the idea of moral truth. Holding a political conception as true, and for that reason alone the one suitable basis of public reason, is exclusive, even sectarian, and so likely to foster political division (129).

Notice the phrase bolded phrase: if reasonable pluralism is permanent, then we should abandon basing political order on the truth rather than the reasonable. If these social and epistemic conditions obtain, views like integralism are bound to be “exclusive, even sectarian, and so likely to foster political division.”

Rawls understood the rationale for integralist-type views. Here’s a passage where he understands why his view is seen as problematic:

I now turn to what to many is a basic difficulty with the idea of public reason, one that makes it seem paradoxical. They ask: why should citizens in discussing and voting on the most fundamental political questions honor the limits of public reason? How can it be either reasonable or rational, when basic matters are at stake, for citizens to appeal only to public conception of justice and not to the whole truth as they see it? Surely, the most fundamental questions should be settled by appealing to the most important truths, yet these may far transcend public reason! (216)

This is precisely what integralists say: it seems obvious that the most “fundamental questions” should be settled by appealing to “the most important truths.” And this might be a suitable basis for political order if not for the fact of reasonable pluralism.

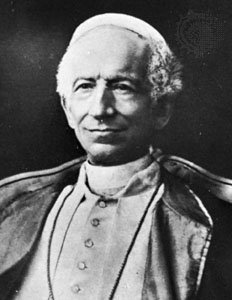

Pope Leo XIII

Interestingly, Rawls associates recognizing the fact of reasonable pluralism as part of being a reasonable citizen, where a reasonable citizen is one who recognizes a moral requirement to propose reciprocal terms of social cooperation: ones that persons with a wide range of views about morality can all accept. The integralist also believes in reciprocity, but does not apply reciprocity to differences of moral opinion. This is why political life comes to be understood as the relation

… of friend or foe, to those of a particular religious or secular community or those who are not; or it may be a relentless struggle to win the world for the whole truth. (442)

And remarkably, Rawls admits the following:

Political liberalism does not engage those who think this way. The zeal to embody the whole truth in politics is incompatible with an idea of public reason that belongs with democratic citizenship. (442)

However, Rawls is mistaken in this passage about his aims: political liberalism does engage the integralist because it makes competing claims about the nature of moral reasoning.

Notice that this point is not lost on all Catholic theologians. To mention one example that will lead the integralist to permanently roll his eyes into the back of his head, consider John Courtney Murray’s remark about Dignitatis Humanae (the Declaration on Religious Freedom, 1965):

A longstanding ambiguity had finally been cleared up. The Church does not deal with the secular order in terms of a double standard—freedom for the Church when Catholics are in the minority, privilege for the Church and intolerance for others when Catholics are a majority.*

Here Murray shares a conception of reciprocity with Rawls because fairness includes fairness between moral perspectives. I think Murray tacitly accepts what Rawls make explicit: that people of good will and virtue can disagree about the requirements of morality, and so to be fair to all such persons, we must propose reciprocal terms of cooperation understood as terms that all can accept.

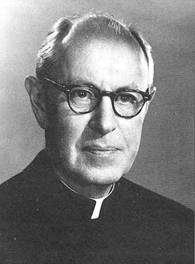

John Courtney Murray

So, this is where I think the divergence between political liberals and Catholic integralists begin: about the rationality of disagreement about the requirements of the natural law between persons of some reasonable degree of virtue.

How should this dispute be resolved? Well, I have quite a few thoughts about the matter, but that’s not the point of the post! The point of the post is that we should probably not ground the difference between the two views in terms of different philosophical anthropologies. You can hold many anthropological properties constant and still disagree about whether moral reasoning leads to dissensus or consensus.

—-

*John Courtney Murray, “Religious Freedom,” in Abbott, ed., Documents of Vatican II, p. 673. See also the instructive discussion by Paul E. Sigmund, “Catholicism and Liberal Democracy,” in Catholicism and Liberalism: Contributions to American Public Philosophy, ed. R. Bruce Douglas and David Hollenbach, S.J. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), especially pp. 233–239.

1 Comment

I wanted to thank you for this article which I thought useful and interesting.

However, I think perhaps there are a few substiles to consider. 1) is the definition that freedom = “The right to decide for oneself what is right and wrong” a correct definition. It is in fact a defined heresy. 2) The major problem seems to be one of defining the ‘reasonable’. As I think recent history fully shows , there need be nothing ‘reasonable’ about liberal democracy, unless of course you call the ruthless slaughter of millions of unborn children ‘reasonable’ . More over continue compromise with those following demonic influence will , sooner or later produce the a society where actual truth, like the physical identity of a human person is replaced with ‘relative truth’ so that those in power can remove from public discourse anyone who actually speaks the truth. I’d love to talk with you about this subject further.

Add Comment